Saltpan Creek

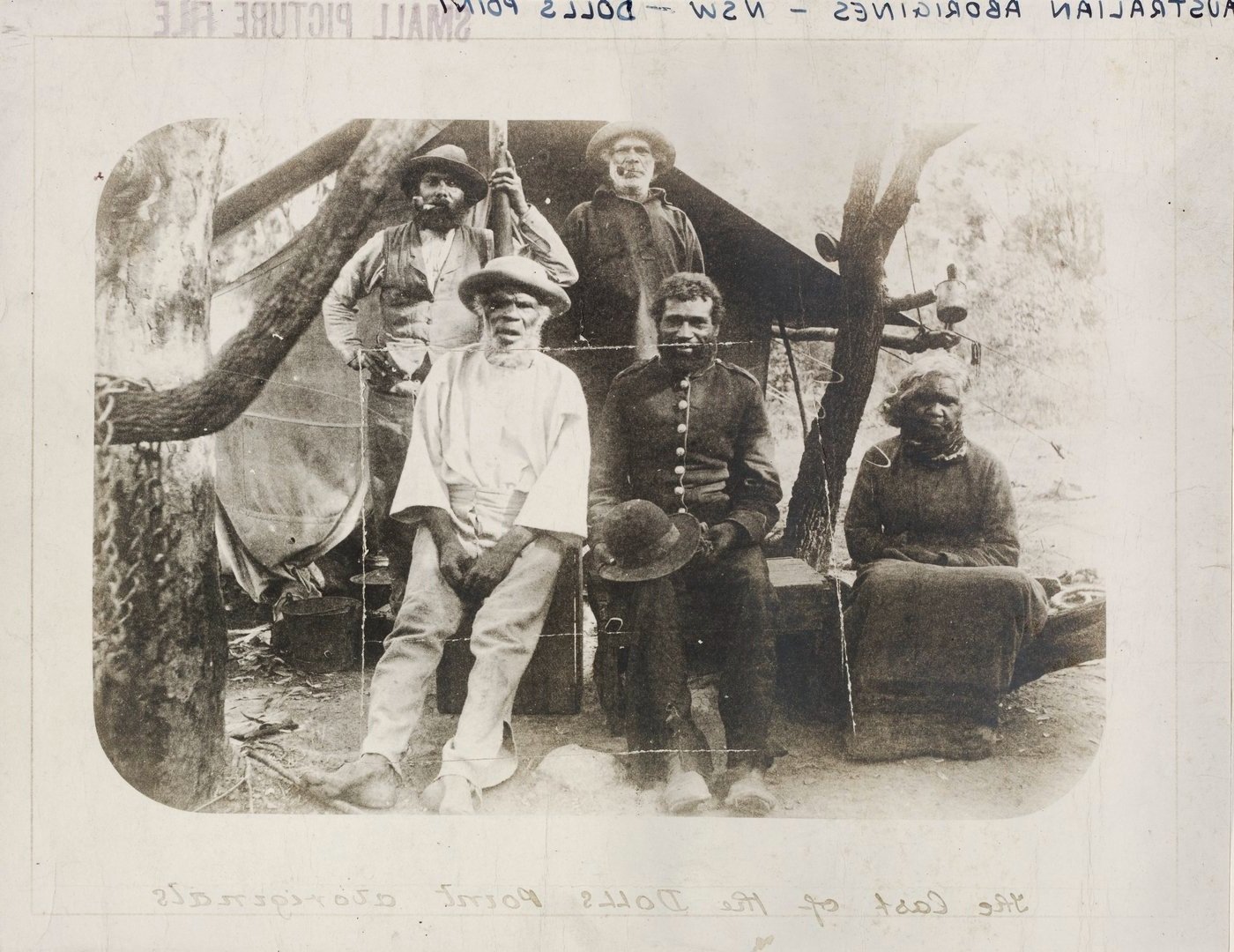

Photo: Titled by unknown photographer, Last of the Dolls Point Aboriginals circa 1890 -1910 - Biddy Giles right

A place of resilience

During the 19th century, the waterways of the Georges River continued to be a place of resilience as Aboriginal people living in the area adapted to changing circumstances following British settlement. In the 1860s, prominent Dharawal Elder Biddy Giles lived on the western bank of Mill Creek in the Georges River area with her husband, Englishman Billy Giles. Born around 1810 into the Gweagal group of the Dharawal people, Biddy lived her whole life on Country - using and trading her environmental knowledge. She facilitated local guided tours for groups of travellers in shooting and fishing parties, sharing knowledge of the waters between Georges River and the Five Islands near Woollongong, teaching about fish and game, and telling Dreaming Stories.*17

In 1891, only very few Aboriginal people were recorded as living in the wider surrounds of Port Hacking, to the south of the study area. One of these was a caretaker and expert fisherman named William Rowley, a Dharawal man from Pelican Point. Rowley worked in a caretaker’s job at Weeney Bay, and made a living selling fish and cuttlebone to settlers at La Perouse.18 In the 1910s, Rowley moved upstream along the Georges River, where he purchased a block of land alongside Salt Pan Creek near what is now Charm Place, Peakhurst. In 1935, Rowley was noted as living at Salt Pan Creek with his wife.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Salt Pan Creek became a centre of the Aboriginal civil rights movement. On the eastern bank of Salt Pan Creek, a block of land next to Rowley’s landholding was purchased by prominent Aboriginal activist Pastor Hugh Anderson and his wife Ellen Anderson (a daughter of Biddy Giles), and later their son Joe Anderson. The property was located around what is now Charm Place, Peakhurst. The Andersons made a living by working in cash jobs, and using their knowledge of flowers and game along the river to sell local produce.19 The Aboriginal families living in the area were able to gather oysters, prawns and fish from Salt Pan Creek, and hunt swamp wallabies and other game.

In addition to the food and natural resources it offered, Salt Pan Creek also provided other important roles. The creek, as part of the Botany Bay catchment area, was a means of transport equivalent to today’s ‘highways’ and also offered connection within the wider landscape: *13

European colonisation had a profound and devastating impact on the Aboriginal population of the Sydney region. In the early days of the colony, Aboriginal people were disenfranchised from their land as the British claimed areas for settlement and agriculture. The devastation of Aboriginal culture came about through disease, invasion and massacres at the hands of British military and armed civilians.

In 1891, only six Aboriginal people were recorded as living in the wider surrounds of Port Hacking, to the south of the study area. One of these was a caretaker and expert fisherman named William Rowley, a Dharawal man from Pelican Point. Rowley worked in a caretaker’s job at Weeney Bay, and made a living selling fish and cuttlebone to settlers at La Perouse.*18 In the 1910s, Rowley moved upstream along the Georges River, where he purchased a block of land alongside Salt Pan Creek near what is now Charm Place, Peakhurst. In 1935, Rowley was noted as living at Salt Pan Creek with his wife.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Salt Pan Creek became a centre of the Aboriginal civil rights movement. On the eastern bank of Salt Pan Creek, a block of land next to Rowley’s landholding was purchased by prominent Aboriginal activist Pastor Hugh Anderson and his wife Ellen Anderson (a daughter of Biddy Giles), and later their son Joe Anderson. The property was located around what is now Charm Place, Peakhurst. The Andersons made a living by working in cash jobs, and using their knowledge of flowers and game along the river to sell local produce.*19 The Aboriginal families living in the area were able to gather oysters, prawns and fish from Salt Pan Creek, and hunt swamp wallabies and other game.

Ellen and Hugh Anderson at Salt Pan Creek, circa 1925 (Source: State Library of NSW).

Families living at the Salt Pan Creek camp, circa 1925 (Source: State Library of NSW).

The Passing of Kings

By the mid-1920’s numerous buildings had been erected on the Anderson’s property including three weatherboard cottages and several sheds, one of which functioned as a small church. The property became an important refuge and camping ground for dispossessed Aboriginal families escaping the brutal regime of the Aboriginal Protection Board. The Andersons reported that in the 1920s and 1930s impoverished white families also camped in the area.*20

The Salt Pan Creek camp on the land owned by Ellen and Hugh Anderson was not a mission or under government control, and as such became an incubator for Aboriginal resistance and agency. Whilst at Salt Pan Creek, Ellen and Hugh Anderson liaised with the Aborigines Inland Mission and met with founders of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) including Fred Maynard and Elizabeth McKenzie Hatton. Numerous families from elsewhere in Sydney and across the state spent time at the Salt Pan Creek camp. In the fight for civil rights, the area became the focus of political activism and knowledge sharing:

Jacko: All them old fellas used to live out there, the Pattens and all them others. You'd see them old fellas sittin around in a ring, when there was anything to be done.

Ted: They were well educated! They could talk on politics!

Jacko: They always DID! Around the kids! No matter where they went!

'Specially when there was anything to do about the Aborigines Protection Board! There was talk about writing a petition. That was always goin' on! Joe Anderson said he'd be talking to the Duke of Gloucester!

Joe Anderson, son of Hugh and Ellen Anderson, grew up at Salt Pan Creek and emerged as a prominent local Aboriginal leader. Joe became known as ‘King Burraga’, a name derived from Ellen’s father, Paddy Burragalang.*21 In 1933, Joe made a poignant appeal from the banks of Salt Pan Creek to King George to extend Parliamentary representation rights to Aboriginal people. The speech was filmed using Cinesound, and is transcribed below:

“Before the white man set foot in Australia, my ancestors had kings in their own right, and I, Aboriginal King Burraga, am a direct descendant of the royal line…

The Black man sticks to his brothers and always keeps their rules, which were laid down before the white man set foot upon these shores. One of the greatest laws among the Aboriginals was to love one another, and he always kept to this law. Where will you find a white man or a white woman today that will say I love my neighbour? It quite amuses me to hear people say they don't like the Black man ... but he's damn glad to live in a Black man's country all the same!

I am calling a corroborree of all the Natives in New South Wales to send a petition to the King, in an endeavour to improve our conditions. All the Black man wants is representation in Federal Parliament. There is also plenty fish in the river for us all, and land to grow all we want.

One hundred and fifty years ago, the Aboriginal owned Australia, and today, he demands more than the white man's charity. He wants the right to live!” *22

Still image from Joe Anderson’s 1933 speech (Source: Australian Screen, 1983. “Lousy Little Sixpence, 1933.”).

Using the most innovative technology available at the time, this speech demonstrates the agency of the Salt Pan Creek camp, and is likely the first appeal for Aboriginal equality by an Aboriginal person to be recorded on film. Many other important Aboriginal leaders and activists spent time at the Salt Pan Creek camp, including Jack Patten, Bill Onus, Bert Groves, Jacko Campbell and Pearl Gibbs, along with Tom Williams (Jnr) and Ellen James - both grandchildren of Ellen Anderson. The site remains an important symbol of the continued struggle for Aboriginal equality.

Every Friday night they used to be spruiking at Paddy's Market. Jack Patten, Bill Onus, Bob McKenzie from Woolbrook, old Joe Anderson, they all lived at Salt Pan They'd only be spruikin' on land rights, that's all, on land rights You know: 'Why hasn't the Aboriginal people got land rights?' That was always the [thing].

Newspaper article describing fare evasion fines given to residents of the Salt Pan Creek camp in 1931, including a poem by Betty Riddell (Source: The Daily Telegraph, 13 June 1931:6).

Land along Salt Pan Creek, which was heavily timbered and low-lying, was deemed unsuitable for colonial agriculture and remained unattractive to subdivision for several decades. These areas survived as open camping grounds for Aboriginal people into the 1930s. Further upstream near the project location in an area that was known as ‘Doctor’s Bush’, Aboriginal families lived in camps and huts until the late 1930s.

Despite the Salt Pan Creek settlement being reported as ‘clean, tidy, and well kept’ in a local newspaper, it was dissolved by the Hurstville Council in 1936.*23 Many of the Aboriginal people who found their home on the Anderson’s property moved further upstream along Salt Pan Creek and settled on the floodplains near Herne Bay now Riverwood. Other families moved on to La Perouse.

Following the Second World War, the Herne Bay housing estate took in numbers of local Aboriginal people along with the wider Australian homeless community. To date, the current Riverwood Estate continues to have dedicated housing for Aboriginal Australians. The work of Joe Anderson is continued today through the work of the Burraga Foundation, which includes in its governance descendants of the Anderson family.

Newspaper article in The Newcastle Sun describing the pending forced eviction of Joe Anderson and the community leaving at the Salt Pan Creek settlement (Source: The Newcastle Sun, 28 August 1936: 2).

Newspaper article in The Newcastle Sun describing the pending forced eviction of Joe Anderson and the community leaving at the Salt Pan Creek settlement (Source: The Newcastle Sun, 28 August 1936: 2).

References

8 Dr Shayne Williams (Burraga Foundation). Project workshop, September 2022.

9 Attenbrow, 2010: 27; Karskens, 2010: 394.

10 John Dickson (City of Canterbury Bankstown’s Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Reference Group. Project workshop, October 2022.

11 Dr Shayne Williams (Burraga Foundation). Project workshop, September 2022.

13 John Dickson (City of Canterbury Bankstown’s Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Reference Group). Project workshop, October 2022

15 National Museum of Australia, 2022.

16 Goodall & Cadzow, 2009: 49-50.

17 Goodall, 2017: 77-78.

18 Goodall, 2017: 78.

19 Goodall & Cadzow, 2009: 121.

20 Goodall & Cadzow, 2009: 122.

21 Goodall & Cadzow, 2014.

22 Australian Screen, 1983. Film can be viewed at National Film and Sound Archive via <http://aso.gov.au/titles/documentaries/lousy-little-sixpence/clip3/>.

23 The Sun, 30 Apr 1926: 14.

With special thanks and acknowledgment to Artefact Heritage www.aterfact.net.au for their creation of the above information in consultation with the Burraga Foundation, as part of the Riverwood Estate Significant Precinct, Connecting with Country Framework, Report to Land and Housing Corporation.